Team-Based Learning (TBL) is a powerful instructional methodology that transforms the focus for class time from the transmission of course content to helping students learn how to use course concepts to solve real-world problems. TBL was developed at the University of Oklahoma Business School in the late 70’s by Larry Michaelsen. We can help you implement it!

TBL has been used extensively in Applied Science in a wide range of courses – from Technology and Society courses to engineering science courses like Aerodynamics, Fracture Mechanics, and Construction Management. The Centre for Instructional Support is now one of the world leaders in the implementation of TBL in Engineering. To learn more about TBL and the implementations in Applied Science you can review:

- Lessons learned from transforming a second-year Mechanical Design course to TBL.

- Lessons learned from transforming a Construction Management course to TBL.

To learn more about TBL visit Learn TBL and Team-Based Learning

TBL – A to Z

This section will help you build your entire TBL course – step by step.

Start with Backwards Design

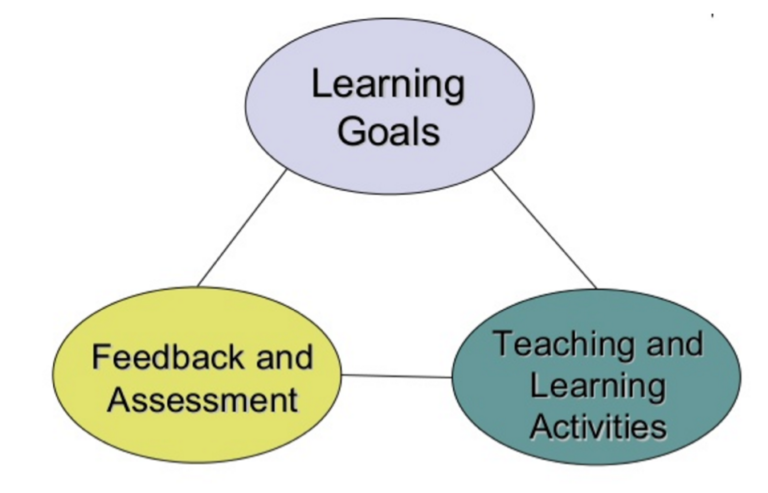

Using Backward Design is essential to developing a good TBL module. First, we need to consider “what I want the students to be able to do” by the end of the module or course, then “how will I know they can do it”, and then “what opportunities do I need to provide to help them succeed”. Dee Fink in his wonderful book, Creating Significant Learning Experiences, reminds us that we must ensure that these three aspects of our course design – Learning Goals, Feedback and Assessment, and Teaching and Learning Activities – are well integrated and mutually reinforcing. We need to develop assessable culminating student performances, in which students can show us all they have learned, and we need to develop teaching strategies that give students learning opportunities to prepare them to show us all they have learned in a culminating performance.

Initial Course Design Decisions

In this initial phase, you consider:

- Your Situational Factors

- Chunk the course into 4-7 modules

- Identify the aims of your modules

- Begin imagining 4S kinds of questions to organize the content

- Develop learning outcomes

Read before you get started:

- Wiggins and McTighe’s Why Backwards Design Is Best

- Roadmap to Creating a TBL module

Chunking your Course into Modules

To start with, first you need to chunk your course into 4-7 chunks. Each piece is usually about 2-3 weeks or 6-10 hours of class time. If you rely on how textbooks are typically organized you might have some trouble imagining only 4-7 chunks. Often textbooks are series of topics that almost implicitly want you to lecture 1 a week…we can fall into this trap because we want to be sure that all the content is covered. But TBL is different. To design a TBL course I would suggest looking at the course topics and trying to come up with alternative organizational schemes or metaphors. Maybe you can build the course around some interesting essential questions.

For example, in a Materials Engineering course, if I were to follow most textbooks…we would introduce one atom, then two atoms, then molecules and crystals, and finally, different materials and equations to calculate their properties….I’m already bored….how about we build the course differently around just two questions…why do things fail? And how do we pick the “right” material for the job? When we reorganize the course around some interesting, concrete questions, ideas for learning activities start to almost automatically come to mind.

Mapping out the Pieces

The typical 2-week TBL module starts with students completing assigned pre-readings or other preparation materials, and then at the first class meeting, they complete the Readiness Assurance Process (multiple choice test). By the end of the Readiness Assurance Process, we have some “assurance” that your students have the required minimum foundational knowledge to begin problem-solving.

The rest of the module focuses on having students use the course concepts to solve problems structured using TBL’s 4S framework. During the problem-solving process, the instructors will sometimes provide very short mini-lectures/expert clarifications when teams are having difficulty progressing.

The module ends with a short instructor-led review of all that has been learned. TBL modules always have the same progression of activities – student pre-class preparation, Readiness Assurance Process, and 4S team tasks.

Imagining Culminating Student Performance

The ultimate goal of any TBL course is to help students learn how to apply course concepts to solve interesting problems. TBL uses the very specific 4S framework to structure the problems to ensure that students do deep analysis, make difficult judgments and decisions, and build justifications and arguments that can withstand the scrutiny of other teams during the discussion following the public simultaneous report.

Great 4S tasks focus on the concrete application of abstract understandings from the readings. You are looking for those kinds of analyses and decisions that experts in your field are routinely asked to make.

During a 4S Application task, students get to concretely apply what they have abstractly learned from the readings. Because of the abstract nature of understanding, it is not “teachable” in the conventional sense. An understanding can be gained only through guided inference whereby the learner is helped to make, recognize, or verify a conclusion. (Wiggins and McTighe, 2013). You want students to connect abstract concepts from the readings with concrete experience during the 4S team Application tasks. Making connections during 4S team tasks is important to consolidate student learning. Helping students see gaps in their knowledge motivates the students to look up what they don’t know and then immediately putting that knowledge into action tests and deepens their understanding. You need to present a scenario that creates the context in which what students “know” abstractly (via their readings) is put to the test when they try to “use” it in concrete, specific cases. Your job is to find or, if necessary, fabricate these scenarios.

Getting Unstuck Activity

Brainstorming what I want students to be able to do” and those concrete disciplinary actions and relating it to the “content I feel compelled to cover” can be difficult and get you stuck – how do you get unstuck?

Take a ledger size page and divide it into two quadrants. Down the right side brainstorm ideas about what you would like your students to be able to do/solve. Down the left side, list all the content you feel compelled to cover in your course. What you are hoping to find are compelling problems to solve, that lead back to the content you hope to cover – this is an iterative process of focusing on the problems, considering what content is really essential or what content might need to be added to allow the students to successfully solve the problems.

Hopefully, significant, interesting, discipline-specific concrete actions emerge that will become the focus for the development of your application activities.

Writing Aims and Learning Outcomes

First, you need to develop your Instructional Aims. Aims are your general instructional intentions for the module. Aims are always written from the point of view of the teacher, the things you hope to achieve as a teacher.

Next, you develop Learning Outcomes. Learning Outcomes focus directly on the students and get more detailed on exactly what the students will be able to do by module end. Learning Outcomes often contain references to the knowledge, skills, and judgement abilities you want your students to develop. These Learning Outcome statements are often the precursors to ideas for 4S Application tasks. When we start thinking about the 4S Application tasks, we want to try to write Learning Outcomes that focus on more concrete actions rather than abstract understanding. We are looking for concrete actions just like a discipline expert takes. Good Learning Outcomes express how experts in your field or discipline would use the course content to solve disciplinary problems. The more concrete you can make the learning outcomes the easier it will be to develop 4S Application tasks from them.

Note below how concrete, active Learning Outcomes use verbs that are already the seeds for 4S Application task development!

Sample Learning Outcomes for a statistics course: by the end of this course students will be able to use their knowledge of statistical principles to:

- Complete a statistical analysis

- Select an appropriate sampling plan

- Develop a survey instrument and plan to gather information from a specific population

Sample Learning Outcomes for a genetics counselling course: by the end of this course students will be able to use their knowledge of genomics to:

- Interpret genome sequencing data

- Identify genetic markers with the greatest risk of disease/abnormality

- Develop a counselling plan to work with specific family issues

Sample Learning Outcomes for a business course: by the end of this course students will be able to use their knowledge of marketing principles to…

- Conduct a market analyses

- Evaluate a marketing plan

- Select or Develop marketing techniques to reach specific populations of clients

Sample Learning Outcomes for a history course: by the end of this course students will be able to use their knowledge of early Canadian history to…

- Interpret written accounts of historical events in light of cultural dynamics

- Assess (and estimate) the bias or orientation of a given author

- Develop arguments for current policies or political positions based on historical context

[Developed by Bill Roberson and Jim Sibley]

Building your Readiness Assurance Process

Buy IF-ATs from Cognalearn

In this phase you need to:

- Select appropriate readings

- Develop a list to topics to test

- Develop a test plan

- Write RAP questions

- Get ready for the classroom

Selecting the Right Reading

You need to identify what specific knowledge students will need to effectively engage with the 4S activities. This is not everything they need to solve every activity but what they require as an entry point to the problem-solving conversation. You do this by mapping back from the 4S application activity to important foundational knowledge that the students will need to be successful. When you are clear on the knowledge students need to know, you are then ready to select appropriate preparation materials.

Next, you need to select appropriate preparation materials. There is an iterative loop with the following step as you refine the concepts to be tested and then select and refine the preparation materials. You can use a variety of preparatory materials including readings, videos, lecture recordings, or narrated PowerPoints.

Over the years we have discovered that less is more with readings. The amount of readings that students will tolerate depends on the particular discipline and institutional context. Our readings are closer to 25 pages for 2 weeks, which is down from our original 75 pages for two weeks. We found that students were spending a short, fixed amount of time completing readings without regard for the complexity and length of readings. Remember the Readings and the Readiness Assurance Process is not trying to be comprehensive. It is just giving students an entry point to the problem-solving conversation.

One aside – when teachers are first introduced to the idea of the flipped classroom, they are often concerned about how to cram their 1-hour lectures into a 10–12-minute preparatory video. This is the wrong way to look at it. These short preparation materials are just to get students started. It is not all that students learn in a module, so 1 hour of lecture content is too much. Students will learn the additional content during the 4S team tasks.

Identifying Topics to Test

Once you have selected readings for the week’s preparation, skim the readings and make a list of critical ideas that students need to get from the preparatory materials. Often after skimming, you can do a slower read, listing important concepts, definitions, and ideas that the student needs to get started. You use this list both to develop questions that check students’ understanding of critical concepts, principles, factual understanding, laws, rules, etc. and to develop a preamble/wrapper for reading, so students know what to pay attention to.

The test should be a mix of approximately 20% remembering (did you do the readings?), approximately 60% understanding (did you understand what you read?), and finally, 20% application. The application questions can be in the form of “Which concept applies to this situation” (are you ready to use what you have read?). To use a book analogy, you want to write these tests more at the table-of-contents level than at the index level.

You can include a few simpler questions that just provide simple accountability that the student has completed the readings. Try to ask about topics that students are likely to interpret incorrectly. Test common misconceptions that might undermine students’ ability to successfully begin problem-solving. You can ask which concept applies to a given situation or scenario. You can focus on the relationship between concepts; this is an efficient way to test two concepts at once.

Writing Good Questions

Multiple-Choice questions have two main parts: the question stem or leader, and the options (which include a correct answer). When beginning to construct a multiple-choice question, write the stem of the question first. A well-constructed stem is a stand-alone question that could be answered without examining the options. The wording of the stem and the verbs it contains determines the overall difficulty of the question.

Bloom’s Taxonomy (lower levels)

Remembering

- recalling, defining, recognizing, listing, describing, retrieving, naming

- Common Question Leaders: How is…? Where is…? When did … happen? How would you describe…? Can you select….? Why did….?

Understanding

- explaining ideas or concepts, interpreting, summarizing, paraphrasing, classifying, explaining, locating, identifying, restating

- Common Question Leaders: How would you classify…? What facts or ideas show….? Interpret in your own words…? Which statement supports…? How would you summarize…? What is the main idea of…?

Applying

- using information in another familiar situation, implementing, carrying out, using, executing, translating, employing, illustrating

- Common Question Leaders: What is the best first step? What is the most significant problem? What would be the worst thing to do? Would it be a mistake to…? What is the most common mistake? Which test would you order next? What is the most common diagnosis? How would you use…? How would you solve it? What is the most logical order? What approach would you use..? What would result if….? What facts would you select to show…?

This next section highlights some of Bill Roberson’s excellent work.

Writing Questions at Different Levels Low-level Questions

- What did the text say? (Remembering)

- What did the text mean? (Understanding)

- How could you apply it? (Recognize an example of a concept)

Low-level Questions that Invite Discussion

- Which statement is most accurate?

- Based on the theory that you just read about, what is most likely to happen if we apply X?

- Which of these items best represents the qualities/characteristics of X?

Higher-level Questions that Invite Discussion

- Based on what you have read about theory A, which of the strategies listed below has the best chance of success, given the specified conditions (X, Y, Z)?

Another Great Question Writing Framework (Gronlund)

ILLUSTRATIVE KNOWLEDGE QUESTIONS

Knowledge of Terminology

- What word means the same as ________?

- Which statement best defines the term ________?

- In this sentence, what is the meaning of the word ________?

Knowledge of Specific Facts

- Where would you find ________?

- Who first discovered ________?

- What is the name of ________?

Knowledge of Conventions

- What is the correct form for ________?

- Which statement indicates the correct usage of ________?

- Which of the following rules applies to ________?

Knowledge of Trends and Sequences

- Which of the following best describes the trend of ________?

- Which is the most important cause of ________?

- Which of the following indicates the proper order of ________?

Knowledge of Classifications and Categories

- What are the main types of ________?

- What are the major classifications of ________?

- What are the characteristics of ________?

Knowledge of Criteria

- Which of the following is a criterion for judging ________?

- What is the most important criterion for selecting ________?

- What criteria are used to classify ________?

Knowledge of Methodology

- What method is used for ________?

- What is the best way to ________?

- What would be the first step in making ________?

Knowledge of Principles and Generalizations

- Which statement best expresses the principle of ________?

- Which statement best summarizes the belief that ________?

- Which of the following principles best explains ________?

Knowledge of Theories and Structures

- Which statement is most consistent with the theory of ________?

- Which of the following best describes the structure of ________?

- What evidence best supports the theory of ________?

ILLUSTRATIVE COMPREHENSION AND APPLICATION QUESTIONS

Comprehension Questions

- Which of the following is an example of ________?

- What is the main thought expressed by ________?

- What are the main differences between ________?

- What are the common characteristics of ________?

- Which of the following is another form of ________?

- Which of the following best explains ________?

- Which of the following best summarizes ________?

- Which of the following best illustrates ________?

- What do you predict would happen if ________?

- What trend do you predict in ________?

Application Questions

- Which of the following methods is best for ________?

- What steps should be followed in applying ________?

- Which situation would require the use of ________?

- Which principle would be best for solving ________?

- What procedure is best for improving ________?

- What procedure is best for constructing ________?

- What procedure is best for correcting ________?

- Which of the following is the best plan for ________?

- Which of the following provides the proper sequence for ________?

- What is the most probable effect of ________?

From: How to make Achievement Tests and Assessments – 5th edition by Norman Gronlund

IF-ATs (aka Scratch Cards)

Immediate Feedback Assessment Technique (IF-AT)

A special kind of scoring sheet, known as an IF-AT form (Immediate Feedback Assessment Technique), is typically used for the team Readiness Assurance tests. IF-ATs are ”scratch-and-win”-style scoring sheets. They dramatically increase the quality of discussion in the tRAT process and, more importantly, provide rich, immediate corrective feedback. Students absolutely love using these test cards. You can expect high-fives and cheering as students complete the tRAT. We have even had some students thank us for the test! If you have not tried these, you must!

These “scratch-and-win”-style answer sheets were invented by Mike Epstein at Ryder University. On an IF-AT form, each question has a row of boxes that can be scratched like a lottery ticket. A small star, exposed by scratching one of the boxes, indicates the correct answer. Students must scratch off the opaque coating one box at a time in hopes of finding the right answer. The power of these cards is in the conversation that students are forced into as they try to generate shared understanding and consensus before choosing which box to scratch. The other powerful feature of these cards is the immediate, corrective feedback.

Decremental scoring is used to induce teams to continue to discuss the questions after an incorrect scratch. One possible point-allocation system for an IF-AT card could be four points for the right answer on the first scratch, two points for the right answer on the second scratch, one point for the right answer on the third scratch, and zero if they needed to scratch off all four boxes to reveal the correct answer. This encourages teams to engage with a question and continue the conversation until they know the correct answer.

Teachers new to TBL often ask how to print IF-ATs to match their tests. Each set of numbered cards already has the stars in a particular pattern and it is the teacher who arranges the answer choices of the test to match the selected card. Cards are available in many different answer patterns to give the teacher flexibility in arranging answer choices and to prevent the students from memorizing or predicting the answers. Each card has an identifying key number on a perforated tab at the bottom that can be removed by the teacher. The IF-AT cards are available in lengths of 10, 25, and 50 questions and with either four options (A-D) or five options (A-E). IF-AT forms are available at cognalearn.com/IFAT. For the use of the Faculty of Applied Science, we provide all lengths of IF-AT cards and please contact CIS for more information.

There have been some alternatives suggested on the TBL listserv:

- “There are also some colour-changing markers that work with invisible ink. You mark the right answer in invisible ink and the students use the marker and know it’s the right answer if the ink changes color. “

- “I recently just made my own IF-AT scratch-off forms since Epstein wasn’t selling them anymore. My classes are small enough that even though it’s a process, it’s still feasible for me to do it (I have roughly 40 students per class). You can do this pretty easily in Microsoft Word. Four cards fit on one 8.5×11 sheet of cardstock. You can’t see through coloured cardstock (at least on the blue and green cardstock we had in our office supply area). Then you can order the scratch-off stickers from Amazon for about $20, cut them into strips, and stick them on the cards. I have a TA who does that part because even though it’s not difficult, it’s fairly time-consuming. This semester is my first time doing these cards and the students love it!”

- “Not sure if folks are aware of the Group RAT site. This is a wonderful site that takes the concept of immediate feedback testing online. Wonderful site, super user friendly (once you learn how to set up your RATs in the right format) A hardy thanks to Gary Theilman for setting up this free site!”

- “I used Qualtrics last year out of necessity during online teaching, and I decided to continue using Qualtrics (instead of scantron and IF-AT) this year by choice even though my university has returned to in-person teaching. The Qualtrics approach works great, and also saves paper“

- “Here is a link with a new iRAT using Qualtrics video that reviews set-up and shows how to add up the scores in Excel: loom.com/share/837689a202f54433a3f5da1827dc1bb4“

See IF-ATs in Action:

Frequently Asked Questions

What are common student complaints about RATs?

Students will say “Testing before teaching makes no sense” – you will hear it, if you don’t properly sell the idea of TBL and explicitly highlight the purpose of the Readiness Assurance Process. These are low-stakes tests that get students ready for the main course – learning how to apply the course content in the Application Activities.

Good students sometimes worry about lower grades on iRATs and voice these concerns. Our iRAT average is typically 65-70% and tRAT averages of 95-100%. Good students sometimes need to be reassured that the RATs don’t count for much, their focus is on learning, and the high team scores will pull up their RAT grades.

How often should I give RATs?

A common early mistake is to give too many RAPs. Giving RAP tests every week is usually too often unless classes are long and only meet weekly. Typically we do a RAP every 2-3 weeks in a regular 13-week course. Remember the Readiness Assurance Process is just about getting students the minimum they need to begin problem solving. The students will learn plenty more during the Application Activities. In certain course configurations with long class meetings once a week, short readings and weekly RAPs can make sense. Better to have too few, than too many – remember these aren’t about testing, they are about getting your students ready for problem-solving.

How much should the RATs count?

Not too much – If you assign a large grade to each RAP, you can turn it into high-stakes testing. Assign just enough to make it worthwhile for students to do the readings and prepare. The typical range for a RAT is 2-5% for iRAT and 2-5% for tRAT. We have always used 1.5-2% for each RAT.

What kinds of questions are good questions for the RATs?

RAP questions are typically constructed at Bloom’s levels Remember, Understand and Light Application. The RAP test highlights concepts more at a table of content level than index level. Remember these questions are just to get students ready for the activities that follow. These are not final summative tests of all that has been learned.

Design and Getting the Most Out of 4S Activities

In this phase you need to:

- Identify the kinds of disciplinary thinking you are trying to promote

- Begin writing 4S scenarios where students apply what they know to analyze a situation and make concrete decisions

- Create facilitation plans

Read before you get started

- Roberson and Franchini’s – Effective Task Design for the TBL classroom

Imagining 4S Possibilities

During a 4S Application task, students get to concretely apply what they have abstractly learned from the readings. Because of the abstract nature of understanding, it is not “teachable” in the conventional sense. An understanding can be gained only through guided inference whereby the learner is helped to make, recognize, or verify a conclusion. (Wiggins and McTighe, 2013). You want students to connect abstract concepts from the readings with concrete experience during the 4S team Application tasks. Making connections during 4S team tasks is important to consolidate student learning. Helping students see gaps in their knowledge motivates the students to look up what they don’t know and then immediately putting that knowledge into action tests and deepens their understanding. You need to present a scenario that creates the context in which what students “know” abstractly (via their readings) is put to the test when they try to “use” it in concrete, specific cases. Your job is to find or, if necessary, fabricate these scenarios.

Example 4S prompts (note the use of superlatives or implied superlatives to force a specific choice)

- A patient comes into emergency with the following symptoms…

- What is the first thing you would do? And why?

- What is the first test you would order? And why?

- What would be the worst thing to do? And why?

- Given 3 possible programs to end homelessness in your city, select the program that is the best and will likely be most strongly supported by local agencies and Civic leaders. (Michaelsen and Sweet)

- What is the most relevant theory that explains the behaviour in the video? (Kubitz and Lightner)

- Which of the following best describes the opportunity cost of coming to class today? (Espey)

- Which of the following should the University do to best increase the quality of Undergraduate education? (Mahler)

- Which sampling scenario would best address this research project? (Mahler)

- Given three valid historical interpretations of the progressive movement, discern which best describes the Progressives revealed in our manifesto. (Restad)

- In Clarence Page’s op-ed piece “The Problem With Trashing Liberty”’ Where does the responsibility for a safe a civil society lie? Which of the following three philosophers (X, Y, and Z) does Clarence Page most agree with on these fronts? (Roberson and Reimers)

- Which of the following passages in the Bhagavad Gita best illustrates reflection about the nature of Krishna’s divinity? (Dubois)

- Rank how useful each source is for understanding the fears of the Cold War era. (Restad)

- Which teacher should be nominated for a teaching award? (Croyle and Alfaro)

- Which indicator (from a list of 5 plausible alternatives) is most critical to making a correct diagnosis in this case? (Michaelsen and Sweet)

- If a moving vehicle overloaded this bridge structure, which component would likely fail first?

- You are making a home assessment, which of the following safety hazards would be of greatest concern? (Clark)

- After assessing Mrs. Randall’s dining room what would be your first recommendation to protect her from falls? (Clark)

- What line on this tax form would pose the greatest financial risk due to an IRS audit? (Michaelsen and Sweet)

- Given a set of real data, which of the following advertising claims is least (or most) supportable? (Michaelsen and Sweet)

- You are consulting for a new business owner who wants to open a dry-cleaning store in Norman, Oklahoma. Where would you recommend locating a new dry-cleaning business? (Michaelsen)

[Developed by Bill Roberson and Jim Sibley]

Writing 4S Activities

First, you may need to make your original Learning Outcomes more CONCRETE.

Next, you need to create problem scenarios/situations where students’ factual knowledge (from the RAP process) is useful, but may be insufficient to solve the problem definitively.

Next, when creating these scenarios you want to clarify exactly what you want students to be doing.

- Evaluate/judge something (object, product, creation, situation)?

- Analyze or diagnose a situation?

- Interpret something (text, artifact, data set)?

- Solve a particular type of messy problem?

Next, identify the concrete information/data sets the students will work with:

- Texts (such as cases, descriptions, excerpts from a textbook, writing samples, etc.)

- Images (visualizations, diagrams, videos, etc.)

- Data (spreadsheets, graphs, charts, etc.)

- Objects (products, specimens, etc.)

Next, you need to pick the format of students’ actions:

- Will they compare?

- Will they sort?

- Will they rank?

- Will they score?

- Will they choose the best course of action?

- Will they distill and represent in a written format?

Next, determine how to make student thinking/decisions visible so it can be represented in a simultaneous report. Can their answer be represented with?

- Colour Voting Cards

- Single Number

- Single Letter

- Single word or phrase

Sometimes this means converting a complex response into a simple response. For example, after a ranking task, ask students to report their #1 choice, rather than their entire ranking scheme. If you’ve asked students to compile a list, ask them to choose the MOST critical item on their list and report it. Every task needs to lead to a moment of sharp differentiation: “I choose this over that.” Getting the students to this moment sets up “WHY?” as the teacher’s entry point for interactions leading to student analysis, reflection, and critical thinking. The simultaneous report naturally lets teams compare their decisions and decision-making process to other teams.

Finally, it is good to develop a facilitation plan for debriefing the 4S Application task, to ensure students learn the most they can from the task. Debriefs always begin by asking ALL teams to simultaneously report their answers/decisions. A good plan provides you with a way to organize the discussion that follows, and direct students into a dialogue with each other.

[Developed by Jim Sibley and Bill Roberson]

Anatomy of a Great 4S Activity

It is recommended that team tasks be constructed to conform to the TBL 4S model. The 4S’s stand for present a Significant Problem, all teams get the Same Problem, teams are asked to make a Specific Choice (constrained choice), and then teams commit to their decision by publically and Simultaneous Reporting it. This framework is not just for TBL teachers. It can be used any time you want to design powerful classroom activities and discussions.

In the TBL model, the structure of the team task gives individuals and their team the opportunity to analyze a scenario, then make a difficult judgment, and finally publicly commit to a decision on an appropriate choice or course of action. This public report of a team’s decision creates an intense reporting conversation where students get specific and timely feedback on the quality of their thinking and their process for arriving at their decision. It is during this reporting conversation you have a facilitation opportunity to help students deepen the discussion by applying the principles of critical thinking.

Example Task

You are head of Engineering for a large dam project on the Yellow River in the Ningxia province of China. The dam is to be located in the Yiling district near the exit of the Ordos Loop section of the river. The dam is to be located at 34°49′46″N 111°20′41″E. The Yellow River is China’s third largest river. The river is characterized by extremely high silt loads, especially in spring floods. The local bedrock is a highly fractured gneiss. The dam will be a concrete earth-fill hybrid design. You have been asked to determine some of the main design parameters, including safety-related questions like what flood event return period to build the dam to withstand.

What flood return period would you recommend the dam be designed to withstand?

- once in 50 year flood

- once in 100 year flood

- once in 200 year flood

- once in 500 year flood

Requiring Complex Analysis

The example looks like a simple multiple-choice question, but it isn’t a simple question. Coming up with a good solution requires the integration and analysis of many different factors and the weighing of tradeoffs (like cost vs. safety). There are a lot of things for the teams to consider in determining a reasonable course of action and coming up with a reasonable defence for their decision.

Important considerations could include:

- How big are the flood events?

- Are changing climate patterns going to affect the size and frequency of flood events?

- What is the difference in cost to design to withstand the different levels of flood events?

- Are there unique landscapes or bedrock concerns? How could we mitigate them?

- What are the population patterns downstream?

- How would downstream populations be affected by a failure at different flood levels?

- How do these kind of dams typically fail?

- Can the dam be constructed to fail elegantly and reduce the threat to downstream populations during flood events?

“Scenarios allow you to embed many variables that can be used to introduce multiple concepts, theories and perspectives into students’ discussion, as well as to complicate the task, if desired, through a mix of relevant factors and red herrings.” (Roberson and Franchini, 2014, p. 287)

Using Concrete Scenarios that Require Concrete Action

We are looking for concrete scenarios that require students to use the concepts and abstraction from the preparatory material to understand, analyze, and solve. The quality of the problem ultimately controls the effectiveness, energy, and learning outcomes of an activity.

“Students, therefore, need to be required to act frequently in ways that generate consequences that provoke reflection and demonstrate visibly their thinking. The more focused and concrete the action, the more visible will be the thinking and the learning—and the more immediately useful will be the feedback.” (Roberson and Franchini, 2014, p. 276)

“Effective team tasks point students consistently toward making decisions that reveal reasoning and understanding in service of a judgment.” (Roberson and Franchini, 2014, p. 279)

“What we know about the nature of learning is that students gain deeper traction, faster, with course content if their first encounters with it include concrete experiences framed by and informed by the abstractions” (Roberson and Franchini, 2014, p. 296)

Using Expert-like Problems

Another nice feature of this example is that it asks the kind of question an expert would need to ask.

“Disciplines are more clearly defined by how those working within the discipline collect, organize, assess, and use information” (Roberson and Franchini, 2014, p. 278)

Students need to use their understanding (gained in the pre-readings, lectures or previous activities) to make expert-like concrete decisions that will have very concrete consequences. You want to design concrete scenarios where conceptual and abstract understanding helps students make better decisions.

“If we want our students to become more expert in our disciplines, we need to structure their encounters with content in ways that change what they can do with knowledge.” (Roberson and Franchini, 2014, p. 278)

Constraining choice to intensify discussion

The example at first glance looks a lot like a multiple-choice question and many teachers worry that constraining choices like this will limit the depth of the discussion. It is quite the opposite, constrained choices focus student energies on the analysis of specific issues, which ultimately helps with team-to-team comparisons that allow students to see how their thinking contrasts with other teams. This really becomes clear for all to see during the public reporting of team decisions.

“The function of the collective decision task, therefore, is to place a restrictive frame around the team’s action. This restriction forces the team to evaluate, integrate and, if needed, respectfully discount a team member’s inputs en route to a judgment and a focused decision.” (Roberson and Franchini, 2014, p. 288)

“Tasks that direct students toward a specific choice do not stifle student thinking but concentrate it so that feedback on the task can be directed at specific, anticipated discoveries and realizations.” (Roberson and Franchini, 2014, p. 290)

More Simultaneous Reporting Ideas

Maps and Push Pins

You are consulting with a new business owner who wants to open a dry cleaning store in Norman, Oklahoma. Where would you recommend they locate a new dry cleaning business (and why)?

- Specific Choice – Push Pin in map

Voting Cards

You are an English teacher. You are working with your students to develop their understanding of the Active and Passive voice. You are trying to develop their next assignment. Which assignment wording would best promote higher-level thinking and a rich reporting discussion?

- List the mistakes that writer frequently make that detract from their efforts to write in an active ‘voice’

- Read the following passage and identify a sentence that is a clear example of: a) active, and b) passive ‘voice’.

- Read the following passage and identify the sentence in which the passive ‘voice’ is used most appropriately.

- Specific Choice – Show Voting Card

Whiteboards

Given the following investment portfolio, investor profile, and market conditions which stock would you sell first and when?

OR

A patient presents at the ER with the following symptoms. What would be your first course of action? What test would you order first?

- Specific Choice – Write decision on whiteboard

Gallery Walks

Sometimes when problems require a bit more writing you can do gallery walks. Student teams present their plans on flipchart paper. This can be effective since it requires teams to distill their decision down to ideas that can be captured on a flipchart and the public reporting helps teams take the task seriously.

Hot Seat Reporting

Use numbered balls to randomly select student teams to report. Teams can display their completed worksheet with analysis using a document camera and walk their classmates through their work. After a few teams, there is often convergence in presented rationales and decisions and an instructor opportunity to provide closure.

Scissors and Glue Sticks

Students bring individually prepared documents and are given class time to distill documents down to a team version. This gets students reading each other work and working with grading criteria to identify valuable parts of each document for inclusion in team submission.

Excel Charts

Given this airfoil shape. What would be the optimal placement for a Pitot tube (airspeed measurement device)? Provide an x/y coordinate.

- Specific Choice – x/y coordinate on EXCEL chart

Stacked Overheads

Given the following x-ray. Identify the most clinically problematic area. Circle the area with a colored pen and be prepared with a rationale to defend your analysis.

OR

You are a consulting geophysicist to a mining company that is looking for new ore deposits on their property. Given these geophysics results, what area of the log is of most interest and what trends are most significant? Identify the most important area and trend.

- Specific Choice – Circle area on transparency, instructor stacks transparencies for simultaneous report

Planning for Class

Planning Class

You should use a lesson-planning model known as SET-BODY-CLOSE to effectively plan each class. This lesson-planning model is described more fully in Sibley and Ostafichuk’s Getting Started with Team-Based Learning (2014, p.123-124).

Here is an example lesson plan structured using the SET-BODY-CLOSE model.

SET

During the SET we set the stage for the class by conveying why the topic is important, how learning this topic has important future utility for the students, how this topic relates to students’ prior knowledge, what the intended outcomes are, and finally set the students to work.

In this case, the class could open with a presentation of the problem task maybe showing images of the river location, images of similar dam types, some examples of dam failures (images, news clippings), and then highlighting how difficult and important these kinds of engineering decisions are to make methodically and systematically. Then the class is carefully put to work – clearly state how much time they will have to complete their analysis and make their decision, remind students that they will be required to publically report their decision, and they will need to be ready to defend their decision and critically examine the decisions of other teams.

Keep the problem displayed during team deliberations and have a timer visible, so teams can budget their time to complete their analysis and arrive at a decision within the allotted time. (Roberson and Franchini, 2014). “Requiring teams to produce an answer—publicly—within a given time helps them maintain focus and also sends the message that “we can’t” isn’t an option. To create an even greater sense of urgency, always allow less time than you think they really need to answer a given question” (Roberson and Franchini, 2014, p. 298).

BODY

This is the major portion of the activity and has the students deliberate within their teams, then make a decision, then publically report their decision (simultaneous reporting) and then be ready for a discussion where their decisions and their rationales will be examined and discussed. The instructor can prepare a discussion facilitation plan to ensure the post-reporting discussion is as productive as possible.

“If you have not anticipated what students’ responses to the task will be, you may not be ready to debrief their decisions effectively.” (Roberson and Franchini, 2014, p. 297)

CLOSE

During the CLOSE we summarize what has been learned. You could perhaps, ask students to list the most important things they learned. Revisit the themes of the SET – why the topic is so important, what the future implications of our decisions could be, and possible next steps or calls to action. Highlight all that has been accomplished and thank students for their efforts.

Using ORID Framework (Stanfield, 2000) to Generate Discussion Questions

You should have some discussion questions ready to gently guide reporting discussions in case they drift to unproductive territory or if the depth of analysis to inadequate. Stanfield’s (2000) ORID framework can be used to generate a series of questions that systematically and methodically examine any issue. But remember the major difficulty for most instructors is they intervening too early. Don’t do it. It can “diminish a team’s sense of ownership of their own responses.” (Roberson and Franchini, 2014, p. 298).

Objective

- What are the facts?

- What sources of information are important to help us make a good decision?

- Where would you like to have more information?

- What assumptions are being made?

Reflective

- Would you be comfortable making this decision with limited information?

- What information would you like to have?

- What should concern us? What tradeoffs need to be considered?

- How has the situation been dealt with in the past?

Interpretive

- Is there another important perspective we aren’t considering?

- What would happen if we changed…..?

- What effects will these changes have? Who else will be affected?

Decisional

- How do you justify your decision? What are your main arguments?

- What was your first choice?

- What was your second choice?

- Was there disagreement inside your team about the best choice?

Facilitation Advice

“The design of a task is ultimately only as good as its execution and management” (Roberson and Franchini, 2014, p. 297).

Many people new to TBL worry about facilitating the discussion after simultaneous reporting. Although we all have much to learn about facilitation, the good news is the 4S structure of TBL activities leads discussions that are simpler to facilitate than open general discussions.

The first thing you do following the simultaneous report is announce the patterns you see…I see mostly A’s and C’s with a few D’s…..then you begin asking teams why they made their decision…..going team to team….building a reasoned argument together with your students.

When teams commit to their positions and publically report it, the instructor can then facilitate the report by simply going from team to team asking “Why did your team pick A” and going to another team “Why did you pick B”. You work the room going side to side and making sure to engage all parts of the room. Try to resist talking to teams next to you. This can become a conversation between the instructor and one team and not a conversation between all teams. One trick is to ask teams across the room to add their two cents. This helps the reporting conversation stay between students and not between the instructor and one team of students. You can ask a team to tell you about their team’s deliberations – what did they talk about, how did you decide…What is nice about this is you are only asking them to recount the conversation, not what is the right answer.

When discussion energy begins to wane you can begin to ask “Why didn’t you pick…” or “Was there a second choice that your team considered?”…” Why do you think someone might pick that choice?” These are the same kinds of questions that you need to use to play devil’s advocate if all the teams agree.

Another important consideration is to close the discussion well. You want to make sure students get reminded of the important takeaways, the assumptions examined, and the inferences that need to be made. You can summarize or even better have the students paraphrase a summary of the discussion. Reflective one-minute paper can be used to great effect here. You can simply ask students to quickly individually list the “3 most important points” or “2 remaining concerns” or “a context where it might not be applicable.” A nice finish to this activity is to have teams compile these points into a team consensus worksheet. However you do it, not closing activities will rob them of some of their value.

From Jim Sibley and Loretta Whitehornes facilitation posterfrom the 2012 TBL conference.

Frequently Asked Questions

What makes a good application question?

Often questions that ask – pick the best course of action from a list of reasonable courses of action. You want the team to use large complex and incomplete data sets, be forced to use inference, make assumptions explicit and use measured judgements to arrive at that “simple” decision. These kinds of analyses can lead to powerful reporting conversations. Remember that the 4 S are not optional. People who are new to TBL, but not new to teamwork often create activities that don’t include some of the S’s. Don’t. The 4S structure lets you consistently generate great activities and reporting discussions. In the interview for my book, people with more TBL experience most often had greater fidelity to the 4S structure. The 4S framework gives you some structure to relax into. When a teachable moment comes by, you are often in a better position to capitalize on the opportunity.

What kinds of questions don’t work for application activities?

The most common problem is questions that are too simple. If a student can sit back and watch the brightest student in the groups solve the problem, many students will do exactly that. This unleashes all sorts of group dysfunction.

Should I grade application activities?

Depends. There is a diversity of opinion on this issue. We have never graded application activities, but we do collect a worksheet from each team after each one. We tell students that the only time we may look at this worksheet is when students are close and want the bump to the next higher letter grade. We have had no issues with students’ willingness to engage in ungraded application activities.

If you do grade the activities, you need clear deliverables and grading rubrics to accurately assess each team’s submission. Many people have started with graded applications because they worried that students would not engage with activities unless they were worth marks. This turns out to not be true and ungraded applications let you turn up the difficulty of the application without the backlash from students when they “get the answer wrong” on graded difficult applications. Remember, the goal here is a great reporting conversation, not getting the right answer.

Developing Your Team Formation Plan

In this phase, you need to:

- Decide on team composition requirements

- Create student sorting questions

- Select a team formation plan

- Be ready to respond to student challenges

Optional Reading

- Assigning Students to Groups for Engineering Design Projects: A Comparison of Five Methods by Brickell, J.L., Porter, D.B., Reynolds, M.F., Cosgrove, R.D.

Team Composition for TBL

- Teams should be five to seven students.

- Teams should be teacher and criterion created.

- Teams should be diverse.

- Teams need to be permanent.

Building Questions to Sort Students

1) Decide Your Sorting Questions

Ahead of time, decide what characteristics would make the course easier or more difficult for a student. For example, previous degrees, work experience, comfort with a certain subject area (stats, math, writing, science, etc.), a specific kind of skill, being from a different culture, having a different native language – anything that might make the course experience easier or more difficult.

2) Prioritize Your Sorting Questions

List these characteristics in order of importance, mixing the “benefit” and “detriment” characteristics together into one list, with the most important characteristic at the top. You must prioritize because many students will have more than one characteristic on your list (e.g., a professional in the field who grew up speaking a different language). Phrase these characteristics carefully, to avoid embarrassing any one group of students.

For example, one anthropology teacher uses “did not grow up in Oregon or any of the immediately surrounding states” instead of “speaks English as a second language.”

Small Classroom Team Formation

In smaller classes with reasonable classroom space, you can simply line the students up. You can use various prompts to quickly order the line, such as:

- I want everyone with work experience at the front of the line.

- With the remaining students not yet lined up, who has a previous degree? Please line up behind them.

- With the remaining students not yet lined up, who has lived overseas? Please line up behind them.

- Everyone else lines up at the end of the line.

Students will often fit into multiple categories, but you will begin the line with the categories that are most important for team success. This is not an exact process and doesn’t need to be. You are creating diverse teams with a range of talents. The questions and criteria you choose to use to order the line depend on who your students are and what assets and liabilities you want to distribute across all teams. Once the students are in the line, you do the simple math of how big the class is and how many teams you can have with five to seven students on each team. Once you know the number of teams you want, you simply count off the teams.

For example, in a class with 42 students, you have decided to have 7 teams with 6 students on each team. Now you would count off from the start of the line: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 until you run out of students. Don’t worry about being exact. The literature shows that randomly-formed teams perform almost as well as teacher-formed teams. So there’s no need to obsess over every last student getting into the exact right group. You might keep track of your most important sort criteria and do a few last-minute shuffles that might be necessary to get teams of equal strength. As an example, in a foundation engineering course, we might shuffle a few people at the end of the team formation process to ensure that each team has both a geological engineer and someone good with math.

This simple procedure has been used with great success in TBL classrooms for over 30 years. It might feel like it takes up valuable class time, but students really seem to enjoy the team formation process, and it is important that students know the teams were formed fairly and transparently. Once teams are formed, students will sit back down with their team, and we will give them a few minutes to do introductions inside their teams. Some teachers will at this point also ask the teams to come up with a team name.

Large Classroom Team Formation

In large classes, it is often impractical or impossible to line the students up around the room. We then use an online survey to gather some student information that is used to order students in an Excel file, for example. We often use online survey tools in a Learning Management System (LMS), such as Blackboard, Canvas, or Moodle, to gather the information. This must be set up as a quiz, since with a survey we cannot trace specific responses to specific students (I will use the word “survey” with the students to stress the non-graded nature of the quiz). We decide on the assets and liabilities that need to be distributed across the teams. We ask a series of questions to find out more about these assets and liabilities in our students. For instance: what is your major? Do you have work experience? Have you lived overseas? We ask whatever questions we feel are necessary to get the information needed to build balanced and diverse teams. Sometimes we want to make sure each team has someone with work experience, someone who is good at stats, or who has a laptop they can bring to class. Once we have the student responses, we perform nested sorts in Excel to order the list, and then we simply count off the teams.

For example, I download the survey/quiz results for the 180 students in my course. Then I build a sort based on the column order that I feel is the most important, first sorting on most important criteria, then on second most important, then on third…etc. This kind of sorting is extremely simple in Excel™. You can sort by multiple columns by simply using the + control on the Excel™ sort dialog box and adding columns in the order from most to least important. Below is an image of the sorting dialog box from Excel™. In this example, I first sort on work experience, then previous degree and finally gender. This lets you in one simple step do a sort that is similar to ordering the line of students in the classroom.

Once sorting is complete, I simply count off on the Excel™ table. In the case of this course of 180 students, I may decide to do 30 teams of 6 students. Next, I would count down the sorted Excel™ results numbering the students 1, 2, 3, and up to 30, and then repeating the 1 to 30 numbering as needed for the entire class list. The list is then sorted into alphabetical order by student name, and the resulting roster of teams 1-30 is posted to the LMS.

When using any team formation method that isn’t done in front of the students, you should inform them of the procedure you used to form the teams. Students need to feel that the teams were fairly created.

Students will need to know where to find their team in large classrooms. To help with this, we create classroom maps that show exactly where each team should sit (see figure below). We post this along with the team assignments on the course website or LMS before the first Readiness Assurance test. We also display this map on the classroom screen when students arrive at the first Readiness Assurance test, so they can find the correct place to sit. In large classes, we have students sit with their teams right from the start. This prevents any disruption at the end of the individual Readiness Assurance Test from students changing seats.

There is one interesting mistake in the above diagram. Can you spot it?

The diagram is built from the instructor’s point of view. When displayed in the classroom, students need to translate in their head left to right and top to bottom to actually locate their team. We now build these class maps with the students in mind.

Frequently Asked Questions

How should I form teams?

Teams should be formed by the instructor. You must resist student preference for student-selected teams. The literature clearly shows that in the long term, criterion-formed teams outperform student-selected teams. When you create teams, you need to think about the student assets that you want to spread across all teams. Maybe each team should have someone with work experience, someone who has lived overseas, or someone who speaks a second language. You need to think about who your students are and what each team will need to have to be successful. Information on the logistics of forming teams in small classes can be found here. Information on the logistics of forming teams in large classes can be found here.

Brickell, J.L., Porter, D.B., Reynolds, M.F., Cosgrove, R.D., (1994) Assigning Students to Groups for Engineering Design Projects: A Comparison of Five Methods. Journal of Engineering Education, 7:259-262

Can I use smaller teams of 3-4?

Teams should be 5-7, really! This is counter-intuitive to most teachers’ experiences using groups where large teams mean some could hide and do no work (known as social loafing). These bigger teams work when you ask the right kind of questions. When team tasks are product-based, small teams are necessary to control social loafing. When team tasks are messy, authentic decisions, big teams work! The teams actually need the intellectual horsepower to solve these big teams.

When I conducted interviews for my book, I always asked questions about team size and have your teams always been that 5-7. I got a very consistent response. People were initially reluctant to use big teams, but on reflection pretty much said the same thing – if I had trouble with a team, it was a smaller team. I now believe in and use the bigger teams.

Should I mix the teams up periodically?

NO – when we first create groups of students there is considerable energy spent on “social overhead” as students work with each other, begin to trust each other, and recognize how to work together, they cohere into a much more powerful team entity that spends a greater portion of their effort on task-focused work. Mixing teams resets teams into groups and they have to cohere all over again. The literature points to 10-14 hours of task-focused work to create high levels of team cohesion. The Readiness Assurance Process and Application Activities all foster team cohesion.

How do I handle students who insist on picking their own teams?

SAY NO – there are a few nice ways to handle this. First and foremost, have your words and rationales ready.

I refer students to: Brickell, J.L., Porter, D.B., Reynolds, M.F., Cosgrove, R.D., (1994) Assigning Students to Groups for Engineering Design Projects: A Comparison of Five Methods. Journal of Engineering Education, 7:259-262. I asked them to write a half-page analysis of why the paper is wrong in recommending teacher-formed groups. If I accept their arguments, I tell them I will let them self-select. No student has ever taken me up on this.

Laura Madson has a nice story she tells. There is a boyfriend and girlfriend on your team, they break up mid-semester – do want to be on that team?

Say NO to self-selection. Be ready for this question and stand your ground.

How do I resolve conflicts among team members?

With Team-Based Learning there often aren’t the kinds of conflicts you see with other forms of group work. Having teams focus on decisions and needing the defend why they made a particular decision really changes things. Give a well-functioning TBL team and bad assignment and you will get dysfunction and conflict, but ask the right kinds of questions (decisions) the right way (4S) and there usually aren’t any conflicts that need managing by the teacher.

Developing Your Peer Evaluation Plan

In this phase, you need to:

- Decide on Peer Evaluation Method

- Select Peer Evaluation Criteria

- Develop and communicate your Peer Evaluation plan

- Be ready to respond to student challenges

Optional Resource

- Approaches to Peer Evaluation: Pros and Cons of Various Methods

Poster by Rick Goedde and Jim Sibley

Select a Peer Evaluation Methods

Peer evaluation is at the heart of keeping students accountable to their teammates for their preparation and contribution to team activities. It is a good idea to carefully explain the evaluation process to the students and perhaps give them a formative opportunity to give each other feedback before the end of the course.

There are a variety of methods that can be suitable in different contexts. You need to consider your goals and contexts to select the appropriate peer evaluation method for your course. Whatever peer evaluation method you choose, it needs to have enough teeth (ability to affect a student’s final grade) to encourage the reticent student to contribute.

Primarily Quantitative

Two methods can be used: a simpler divide-the-money evaluation and a more rigorous rubric-based evaluation.

In rubric-based evaluations, students rate their teammates’ behaviours using Likert scales on a series of questions about the team experience. Typical rubric criteria include:

- Preparation: did your teammates come prepared?

- Participation: did your teammates come to class?

- Contribution: did your teammates contribute to team success?

In simpler “divide-the-money” evaluations, each person is given a fixed sum to divide amongst team members. A typical evaluation prompt might be: “Your project team has received a $1,000 bonus. Divide the bonus amongst your teammates based on their contribution to the project.”

Fink Method

A multiplier is created from the peer evaluation scores and that is used to adjust the overall course grade for a particular student.

Some examples will likely help.

Example 1

In the case of a high-performing student, where the team’s average peer evaluation score might be 10 and that particular student has received an 11 overall, the individual score is then divided by the average peer evaluation and yields 1.1. This is then used as a course multiplier. Therefore the student receives 1.1 times the unadjusted whole team grade (e.g. 80%), adjusting their grade upwards to 88%.

Example 2

In the case of an underperforming student, where the team’s peer evaluation average might be 10 and that particular student might have received an 8, their score is then divided by the average peer evaluation and yields 0.8, which is then multiplied by the team grade. Therefore the student receives 0.8 times the unadjusted whole team grade (e.g. 80%), adjusting their grade downwards to 64%.

Michaelsen Method

A separate team maintenance score (usually 5% of course grade) is created from evaluation results for each student.

The decision to use the Fink or Michealsen method often rests on the percentage of the course grade that is allocated to team products. When the team products make up a significant portion of the overall course grade, it can make sense to use the Fink/Michaelsen Method.

Primarily Qualitative

University of Texas Method

Focuses on providing students with valuable written feedback on their performance (it is not used to adjust student scores). Students are asked to reflect on two prompts for each of their teammates – one thing I appreciate about you and one thing I request. This has similarities to the CONTINUE-STOP-START method. I would like you to CONTINUE to….I would like you to STOP…..I would like you to START….

Koles Method

A hybrid between the University of Texas Method and the Fink/Michaelsen Method. It incorporates both formative written feedback and summative evaluations of performance. Also gives extensive feedback on the quality of the feedback you give your teammates. Paul describes this as a lot of work, but one of his favourite parts of the course each semester.

For more information read the chapter on Peer Evaluation in Getting Started with Team-Based Learning

Pick your Peer Evaluation Criteria

Here are the 3 most common:

- Preparation: did your teammates come prepared?

- Participation: did your teammates come to class?

- Contribution: did your teammates contribute to team success?

Here are other possibilities:

- Fosters good team climate

- Facilitates contribution of others

- Completes tasks on time

- Responds well to conflict

- Displayed positive attitude

- Was consistently helpful

- Expressed thoughts clearly

- Reacted sensitively to non-verbal cues

- Worked hard

- Was dependable

- Overall, a valuable team member

Paul Koles Prompts

Cooperative Learning Skills:

- Arrives on time and remains with the team during activities

- Demonstrates a good balance of active listening and participation

- Asks useful or probing questions

- Shares information and personal understanding

Self-Directed Learning:

- Is well prepared for team activities

- Shows appropriate depth of knowledge

- Identifies limits of personal knowledge

- Is clear when explaining things to others

Interpersonal Skills:

- Gives useful feedback to others

- Accepts useful feedback from others

- Is able to listen and understand what others are saying

- Shows respect for the opinions and feelings of others

Helpful Software

You can use online software to streamline the task of peer evaluation. Often you can set the software up in September and collect the results in April.

iPeer

This free open software was developed at the University of British Columbia and allows you to entirely automate the peer evaluation process. It supports several different evaluation types and has a building block integration with Blackboard Learn. The software needs to be installed on a local server and is based on the typical LAMP stack (this means sometimes to your IT group). You can learn more about it here and download it for free here. This is a good choice for countries with strict privacy laws. In my home province of British Columbia, Canada – any student data needs to be stored on Canadian servers.

CATME

This free US-based web service lets you easily set up peer evaluations for your class. The only catch is you give them the right to do research on the anonymous aggregate evaluation data.

Teammates

This free Singapore-based web service lets you easily set up peer evaluations for your class. This software is relatively new but looks extraordinarily promising.

SparkPlus

This inexpensive Australian-based web service lets you easily set up peer evaluations for your class. This software was developed by Mark Freeman from the University of Sydney Business School to support his TBL courses.

Accountability, Feedback, and Grades

In this phase, you need to:

- Decide on your grading scheme

- Consider having students set grade weights

Accountability

There are three things we should do to encourage productive student behaviours in the TBL classroom.

- Students must be encouraged to individually prepare.

- Students must be encouraged to contribute to their team.

- Students must be made aware that they will be accountable for their contributions to their team.

In order to accomplish these goals, we must incorporate three important corresponding measures into the overall course design to ensure that we encourage the behaviours we want. These are:

-

- Individual performance

- Team performance

- Contribution to the team

An important measure of an individual’s performance comes from the individual Readiness Assurance Test scores. These scores give instructors a measure of individual accountability for the quality and completeness of each student’s preparation. This component must be a substantial enough portion of the final grade so that a student feels compelled to prepare, but not so large that the Individual Readiness Assurance Test (iRAT) turns into high-stakes testing. There are often other measures of individual performance that are not related to TBL, including individual assignments, midterms, and final examinations. Students are sometimes shocked at first at the low individual scores on the iRATs. Typical averages are 65-70%; that’s perfectly normal. Students may need to be reassured that the RATs are working as designed, that they constitute only a small portion of their final grade, and that the higher team grade on the tRATs (typically 85-95%) will balance out the lower iRAT score.

The team performance measures come from all team activities that are graded. These include the team Readiness Assurance Test scores and, in some courses, the Application Activities.

The measure of a member’s contribution to their team typically comes from a peer evaluation process. Peer evaluations hold students accountable for their level of participation. Peer evaluations also reassure students that loafers won’t benefit from the typically higher team grade; this is a happy side effect of the process.

Typical Grade Schemes

There is a wide range of grading schemes found in different Team-Based Learning courses. Course context, institutional culture, instructor goals, and course goals all need to be considered when you construct the grading scheme that is appropriate for your course. In some institutional environments, policy or local norms may not tolerate having a grade component like peer evaluation where students evaluate other students. For example, in some very competitive environments such as pre-med, it can be very difficult to sell a grading scheme that incorporates any summative peer evaluation process where one student assesses another student in a way that affects their final course grade. In these environments, the formative styles of peer evaluation are more commonly implemented, since they don’t affect students’ grades directly.

One of the big decisions here is whether to grade 4S tasks. There is no consensus on whether 4S tasks should be graded. Those that don’t grade are happy with the level of engagement and like that, they can ratchet up the difficulty of tasks without upsetting the students too much. Other people do grade the 4S tasks and are happy with the process. You need to make this decision for yourself and your context. A place to start is searching the TBL listserv archives about the merits of grading or not grading activities. There have been many good discussions about this on the listserv.

The TBL grade component in a prototypical TBL course with ungraded Application Activities (i.e. only iRAT and tRAT grades) can be as low as 25%. In these courses, the other 75% of grades might come from traditional components like individual essays, individual reports, midterms, and finals. There is considerable range on how TBL course grades are divided between individual and team work in different courses and contexts. In some courses, the grades are 100% based on TBL; these courses most often have graded Application Activities.

Grading Scheme in course with ungraded 4S tasks

TBL Components (25%-35%)

- Individual Readiness Assurance tests (10%-15%)

- Team Readiness assurance tests (10%-15%)

- Peer Evaluation (5%)

Traditional Components (65%-75%)

- Midterms

- Final Examinations

- Individual Assignments

Student Grade Weighting Activity

Many TBL practitioners use a grade weight setting exercise in a class early in the semester. Letting students have a say in grade weight setting can help with student “buy-in” to TBL.

Instruction to Students

Representatives of the teams will set the percentage of the course grade that will be determined by scores in each of the major performance areas (Individual Performance, Team Performance and Team Maintenance) during the first class period. Team representatives will also decide on the relative weight of the Readiness Assurance Tests vs. the final exam within the Individual Performance area. Grade weights will be set for the class using the following procedures:

1) Each team will set preliminary weights and select a member to meet with other teams’ representatives.

2) Team representatives will meet in the center of the room and develop a consensus (i.e., every representative has to be in agreement about the grade weights for the class as a whole.)

3) The only limitations on your grade weight decisions will be that:

- a minimum of 10% of the total grade must be assigned to each major performance area.

- within the individual performance area, at least 50% of the grade must be based on the final exam.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are common student concerns about grades?

In any kind of group work, students often have concerns that their grade depends on their less capable peers. That is one reason to keep the TBL portion of the course grade modest. In most of our TBL courses, the TBL portion is only 25% and the other 75% is traditional things like individual assignments, midterms, and finals. In that 25% portion, it is often 10% iRAT, 10% tRAT and 5% peer evaluation. If you have 5 modules with 5 Readiness Assurance Processes then individual iRATs are only worth 2% a time and tRATs are only worth 2% a time.

How do I handle students who don’t participate or “free ride”?

It is not a problem. This problem actually disappears when we get the task right. When an instructor comes to me with this problem, the first place we look for the source of the problem is the assignment itself. Team-Based Learning could easily be called decision-based learning…teams are naturally pretty good at decisions (think of courtroom juries). Large product-based assignments often spawn group dysfunction. If I am a C student and want a C at the end of the course and you are an A student…you are likely going to be unhappy with the quality I do….does the A student step in and redo the C student’s grade? This will likely make everyone in the group unhappy. Get the question right and everything seems to fall into place.

Is peer evaluation really necessary?

Absolutely – the peer evaluation process needs to have enough teeth that good students are rewarded for their work and students who don’t prepare as well or don’t contribute don’t benefit from the higher team grades.

Getting Ready for Learning

In this phase, you need to:

- Plan your first day of class

- Get yourself in an experimental and playful mood

Helpful Resource

- First Day Orientation Activity by Gary Smith

Getting Students Ready

Beginning the Course Well

How you start — specifically, the tone you set and how you orient your students — can determine student acceptance and satisfaction with TBL. Before getting to the classroom, you should spend some time getting your own rationales and understanding of TBL well organized. Make sure you can answer the deceptively simple student question, “Why are you using TBL?” When you truly understand your own reasons, you are in a much better position to communicate to your students how the TBL classroom works and how TBL will greatly benefit them and their learning. If you fail to properly orient your students or fail to convince them of the value of using TBL, then you are at risk of increased student resistance.