Why Consider Flipping Your Classroom?

A flipped classroom is a pedagogical model that reverses traditional lecture and homework elements. Students engage with course materials and lectures such as online videos out of class in preparation of an active learning experience during class time.12 The current understanding of a flipped classroom is associated with students engaging with materials online followed by in-class activities which may include small-group work or peer learning.3 Flipping the classroom can improve students’ understanding of course content beyond basic knowledge and memorization. It can also serve more diverse populations and create more inclusive opportunities due to its variable nature by providing different activities, media, and opportunities for students to participate.4

Activities can include discussions, debates, clicker questions, Q and A, demonstrations, simulations, peer tutoring and feedback, and role playing. The instructor can choose to flip all classes, or flip a few classes in a semester, where the concepts can lead to active learning experiences. Before the learning activities are organized, instructors should first determine the objectives of their course.5 Read the section below for more information on the advantages of a flipped classroom.

Benefits of a Flipped Classroom

A flipped classroom allows students opportunities to work and collaborate on meaningful tasks, while receiving immediate feedback from their peers and instructor.6 As most students’ attention begins to drop after ten to fifteen minutes, the flipped approach motivates students to stay focused during the entire in-class period. Before coming to class, students have time to process course content and improve their understanding, and during class, they engage in active learning which leads to better retention of concepts compared to traditional lectures.7

Some benefits of a flipped classroom to consider can be found below.

1. In a flipped classroom, instructors and TAs can get to know students better. When instructors experience an increase in interaction, they can have a better understanding of students’ learning needs.8 Instructors can provide more individualized help during an in-class session as they can be a “guide on the side,” instead of a “sage on the stage.”9

2. In-class activities have a greater degree of flexibility since lectures are pre-recorded. If technology interferes with a synchronous class, students are less likely to fall behind.10 Students can have more flexibility in terms of the pace, time, and place of learning with the online materials as students can review lecture recordings multiple times to write down more detailed notes on difficult concepts. Some students may also find it helpful to rewatch lectures when preparing for the final exam.11

3. The flipped approach also gives students opportunities to practice critical thinking skills and engage with complex issues and questions.12 Active and peer learning during class helps students achieve deeper understanding and better retention of concepts, which creates opportunities for higher learning.13 A flipped classroom offers more opportunities for deliberate practice and better support for students when they encounter more challenging problems and concepts.14

4. Due to technological advancement in recent years, there is an increasingly wide range of options that can facilitate content delivery, including videos, podcasts, and lecture capture, which allows students to access knowledge in different ways. Students have also reported that they prefer classes that have online components.15

5. Even though a greater amount of time is necessary to prepare online materials, instructors can reuse the online content if the same course is offered in the following year.16

Below are some examples of questions that can be incorporated into team-based learning activities within APSC. Although the options provided seem simple, the process to identify an answer, and the justification required to support the choice, can allow the instructor to facilitate in-depth give-and-take discussions. Teams can also get immediate feedback from other teams regarding their thought processes after they explain their decisions.17 Visit this page on our website for more details on team-based learning.

You are head of Engineering for a large dam project on the Yellow River in the Ningxia province of China. The dam is to be located in the Yiling district near the exit of the Ordos Loop section of the river. The dam is to be located at 34°49′46″N 111°20′41″E. The Yellow River is China’s third largest river. The river is characterized by extremely high silt loads, especially in spring floods. The local bedrock is a highly fractured gneiss. The dam will be a concrete earth-fill hybrid design. You have been asked to determine some of the main design parameters, including safety-related questions like what flood event return period to build the dam to withstand.18

What flood return period would you recommend the dam be designed to withstand?

- Once in 50 year flood

- Once in 100 year flood

- Once in 200 year flood

- Once in 500 year flood

A patient who received spinal anesthesia four hours ago during surgery is transferred to the surgical unit and, after 90 minutes, now reports severe incisional pain. The patient’s blood pressure is 170/90 mmHg, pulse is 108 beats/min, temperature is 37.2oC (99oF), and respirations are 30 breaths/min. The patient’s skin is pale, and the surgical dressing is dry and intact.19

The most appropriate nursing intervention is to:

- Medicate the patient for pain

- Place the patient in a high Fowler position and administer oxygen

- Place the patient in a reverse Trendelenburg position and open the IV line

- Report the findings to the provider

An architect is designing a replacement roofing system for an existing building in a hospital complex. The hospital is worried about the effects of the installation of the roof on patients with breathing difficulties. The hospital has asked the architect to choose a roofing system that minimizes health risks.20

Which roofing system should the architect specify?

- EPDM

- Modified bitumen

- Four-ply built-up roof

Planning theory can be divided into two general areas: substantive planning theory and procedural planning theory. Elaborate on this distinction and give examples of each. Are there connections between the two, or are these really two quite distinctive sets of theories?21

This figure compares traditional lectures with a flipped classroom approach. In a traditional lecture, students receive their first exposure of the material and complete assignments after class. In a flipped classroom, students work on activities to apply their knowledge.

Models of Flipped Classrooms

Thinking of applying the flipped classroom approach to your course? Check out the different models and potential learning activities below for some ideas.

Standard Flipping

What it looks like:

Lectures are recorded and students watch the lectures as homework. During class time, students complete problem-solving activities in groups.

Potential Learning Activities:

In-class activities are highly interactive activities that include in-class discussion, group work, or working with other students using shared documents. For example, the instructor can create a poll to determine student understanding of concepts and encourage discussions.22

One-Day-a-Week Flipping

What it looks like:

Flip one lecture a week if a standard flipping is not appropriate for the course. Students watch short lecture videos to prepare ahead of time and work in groups during class to solve real analytical problems.

Potential Learning Activities:

For example, the instructor can record a short lecture video that students have to watch before class. In the in-class session, students form groups to solve analytical problems together. The correct answers are then shared in class and the students make adjustments to their own solutions.23

Selected-Content Flipping

What it looks like:

The instructor needs to be selective and strategic about what to record for students to watch before class. The instructor can record only a few topics and reserve some class time for delivering lectures on difficult topics.

Potential Learning Activities:

For example, which concepts or topics do students usually have difficulties with? The instructor can create more class activities that focus on these concepts. The instructor can also record lectures that can be reused in the following semesters.24

Flipping Without Recording Video Lectures

What it looks like:

A common misconception about flipped classrooms is that pre-recorded lectures are a necessary component. However, instructors can utilize other materials so students can learn the course content.

Potential Learning Activities:

Other materials include PowerPoint presentations, readings, podcasts, and videos that have been recorded by others.25

Full Hybrid Flipping

What it looks like:

Instructors using this structure can completely remove in-class lectures and replace them with time for students to work on out-of-class activities.

Potential Learning Activities:

For example, students can watch the lecture recordings out of class.26

This figure displays students’ learning process of the flipped classroom approach, including the ways that students can explore course concepts, reflect on their learning, and demonstrate their knowledge.

Diagram adapted from Flipped Classroom: The Full Picture for Higher Education, a post on Jackie Gerstein’s “User Generated Education” blog.

Characteristics of Effective Teaching in a Flipped Classroom

When planning a flipped classroom, the following characteristics are important to consider:

Interaction and Involvement

Students need opportunities to participate and interact with the course content and become actively involved in the learning process. A flipped model can provide opportunities for active learning and for instructors to respond to students’ questions and needs.27

Tip: To improve accessibility in your courses and ensure students have equal access to education, please visit the Accessibility in APSC page on our website for more information.

Communication and Clarity

The instructor needs to clearly communicate course content by explaining complex topics in a way that is easy to understand. To do this, the instructor can record mini lectures that include examples, stories from the field, and analogies. The purpose of each individual session and the course needs to be clearly communicated by the instructor at the start.28

Enthusiasm and Expertise

To create a positive learning experience, the instructor should display enthusiasm, expertise, and confidence in their knowledge of the field.29

A Student’s Experience in a Flipped Classroom

“I took a course on research methods which adopted the flipped classroom approach, and I greatly enjoyed it. Incorporating online resources and self-directed learning components was helpful for me when I reviewed difficult concepts. It gave lots of flexibility to rewatch video lectures and review the slides posted on Canvas by my professor. I also enjoyed doing the active learning activities during class, which encouraged greater interaction in my team.”

Constance Lau, third-year BA student and CIS Learning Technology Rover (September-December 2024)

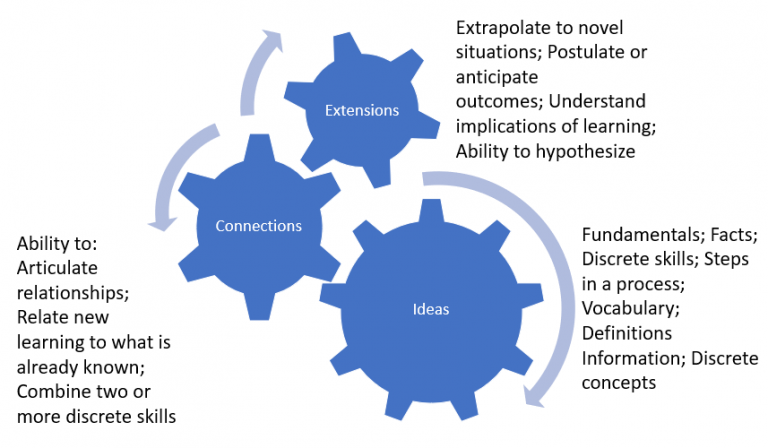

The ICE Model

The ICE Model below provides a framework that demonstrates how the characteristics of effective teaching can be implemented in the classroom.

The ICE model, developed by Sue Fostaty Young, is an acronym for Ideas, Connections, and Extensions. They are three qualitatively different frames of learning. In this image, each frame is an interconnected cogwheel, which illustrates that changes which occur in any one frame of learning will affect the other two frames.30

Adapted from Chapter 1. Introduction to the ICE Model 1.1 Getting Started in Teaching, Learning, and Assessment Across the Disciplines: ICE Stories edited by Sue Fostaty Young and Meagan Troop

I – Ideas

Ideas are the bits and pieces of learning, and they are typically made up of disciplinary vocabulary, basic facts, discrete pieces of information, and steps in a process. If the student can find the information in their textbook or notes, it is an idea. For example, remembering events, names, and dates in a history course is a demonstration of Ideas-based learning. In a math class, successfully completing “plug and chug” equations is representative of Ideas-based success.

C – Connections

There are two kinds of Connections: content-related connections and connections that require the student’s personal meaning-making. For example, math students can analyze the key points of a problem and choose relevant equations. Instructors can consider what type of learning they expect from students and their teaching context in order to identify Connections.

E – Extensions

Students identify the implications of the content they have learned and use these concepts in a completely different context beyond the classroom. For example, in a math class, having the ability to make Extensions allows students to come up with a new equation that solves an unfamiliar problem.

How to Plan a Flipped Classroom

Regardless of the model you choose to implement, there are three general stages to consider when planning a flipped classroom for your students: introducing the task, the out-of-class task, and how you are going to assess students’ learning.

Introduce the Task

The purpose of this stage is to increase the level of student participation in the class activities that students will be completing. The instructor can introduce the tasks by clearly outlining their expectations for how much time the students will need to invest to be ready for the class activity and what the students will be doing during class. It is crucial to explain why students need to prepare for the class activities and what the activity will be. Active learning during class time will be a new experience for some students, so a “no surprises” approach can help students ease their anxieties about a flipped class.31

Teaching students how to use online materials out of class is important as students cannot ask questions in the same way as they would in an in-person lecture. Instructors can remind students about the importance of note taking.32 This is because students can write down their thoughts and questions about the course material when they are watching the online learning materials and later bring their notes to class. During class, students can ask the instructor for clarification on difficult concepts based on their notes or discuss with their classmates.

Creating a rubric to outline the assignment outcomes and how students will be graded will also encourage students to make a learning plan for themselves, especially for courses that have significant online components.

Out-of-Class Task

It is recommended to consider the choice of media for online activities and materials. For example, instructors can produce their own learning materials such as podcasts, narrated PowerPoints, and screencasts, or use content found online such as readings, videos, and websites. The suggested length of video content is 10-15 minutes. Including prompts and guiding questions in the videos can help students understand the key objectives of the preparation tasks that were done before the class. If students submit questions about the content before class, instructors can discuss these topics during the class.33 Besides recorded lectures, pre-class readings and a quiz based on this reading can also be assigned to students.

The instructor can also include peer feedback and online discussions as part of the online assignment, such as asking students to respond to their peers’ responses in a reading assignment. Peer feedback encourages a dialogue on student work and allows students and the instructor to focus on the process, instead of the final work. This also ensures that students receive ongoing feedback throughout the term. Asking students to participate in online discussions can encourage them to find and draw connections to useful online information.34 The instructor can also consider revising the online materials by incorporating student feedback.35

Tip: If you would like to narrate your PowerPoint slides, we recommend using Camtasia, which is a desktop-capturing software that includes video editing functionalities. Please visit the Teaching Tools and Resources page on our website for more information.

Tip: It is recommended that large online assignments are broken up into smaller assignments and staggered deadlines are set throughout the process.36

Assess the Learning

There are benefits to the students and the instructor if they know whether the students are adequately prepared for the active learning activity during class. Methods of assessing the level of student preparedness include self-assessment quizzes or low-stakes online quizzes, which are ideally short and include questions that allow students to apply their knowledge. The instructor can also include opportunities for students to ask questions and provide formative feedback on the assessment questions. Other ways to assess whether students are adequately prepared include doing a short assignment at the beginning of the in-class session.37

Incentives for working on out of class or online assignments can increase student motivation. For example, instructors can require students to complete a pre-class quiz for reading assignments, and the quizzes can count towards students’ final grade. Instructors can also carry out a short quiz at the start of class and give students extra points if they provide correct answers.38

In-Class Activities

Activities that introduce opportunities for student-instructor dialogue, peer-to-peer learning, and opportunities for active learning are valuable because they promote deep learning. The objectives of in-class activities should be connected to course assessments and objectives. During class time, the activities should encourage students to be creative and open to making new discoveries.39 Giving students class time to work on assignments gives the instructor opportunities to give regular feedback. This also allows students to ask peers or the instructor for clarification and feedback.40

Examples of class activities that can enhance learning in APSC:

In Engineering, activities that can enhance experiential learning include building prototypes out of plastic, metal, or wood.

In SALA, active learning activities may include investigating, discussing, and creating with groups. Students can collect information about the topic, share this information with their group members, and finally create a group presentation.41

In Nursing courses, students can participate in problem-solving activities, group discussions, or review exercises.42

In SCARP, the flipped classroom model can include group or individual activities, such as scenario simulations or games during class.43

Motivation

Student motivation is crucial to the entire learning process and can be affected by the design of the activity. An enthusiastic instructor who has a positive relationship with students and creates an open and relaxed atmosphere in class can motivate student learning and participation.44 Learning activities that are achievable but challenging can motivate students, especially if they know that the course is connected to their future success and if they find personal meaning in engaging with the material. Positive feedback from the instructor can also motivate students to complete their learning.

The instructor can instill accountability for pre-class tasks by explaining that not doing the activities reduces the value of in-class learning activities for the students themselves and the peers they are working with. Setting up ground rules can help the instructor clarify expectations for students.45

In-Class Activities

In a flipped classroom, there is an in-class portion and out-of-class portion. To determine whether in-person or online activities are a good fit for your class, in-person activities are generally best carried out during the in-class portion, and online activities are usually completed by students before each class.

After the instructor has designed and prepared the activities for the in-class session, the instructor’s primary role is to support, guide, and monitor the learning process of students. Because students will have different levels of comprehension after completing the out-of-class task, the instructor can assess students’ understanding in an online environment and organize individual or group-based activities during class time.46

Individual Activities

If your students have conveyed difficulty with understanding the concepts out of class, individual activities can be beneficial. Individual tasks taking place before group activities can help students with more challenging group activities and those who need individual reflective time to understand the content.47

IClickers

Time on task: 5 to 10 minutes; Group size: 1 to 2

IClicker gives students immediate feedback regarding concepts they learned out of class. It can also be used to create polls for students to indicate their answers. Creating multiple-choice questions can determine whether students have fully understood the out-of-class content.48 Students can download the iClicker App on their phones to participate in iClicker quizzes or polls. They can also review questions asked during class and view the correct answers in the iClicker app.49 Using the online version adds more flexibility.

Wordwebs/Concept Maps

Time on task: 30 to 45 minutes; Group size: 1 to 4

Concept maps can be completed individually or in groups and can reinforce concepts learned out of class. Students can make connections between concepts by mapping out how ideas are thematically related.50

Individual Problem Solving

Time on task: 5 to 10 minutes; Group size: 1 to 4

Problem-solving activities that are completed during class give students the opportunity to tackle problems with their peers. The instructor can provide guidance or support if challenges arise. Immediate feedback can be provided by the instructor to address misconceptions.51

Group Activities

The objective of the in-class session is often the completion of group activities. Students can bring their individual understanding of the material to class and during class time, they can draw on their group members’ knowledge of the content to better recall the concepts and develop new understandings.52 If group work is incorporated into the course, it is recommended to give students time in class to work on their group projects, which reduces the inconvenience of organizing meetings after class and gives the instructor the opportunity to check on students’ progress.53

Think-Pair-Share

Time on task: 5 to 15 minutes; Group size: 2

In the Think phase, students work individually to flesh out their thoughts and write them down, and then they discuss with a partner in the Pair phase. In the Share phase, the instructor elicits responses from the entire class and engages students in a wider discussion to demonstrate various perspectives.54

Affinity Grouping

Time on task: 30 to 45 minutes; Group size: 3 to 5

Students write down ideas individually and then discuss the ideas in a group to determine how to categorize the ideas. This exercise helps students stay on the same page as their group members before they complete more challenging in-class learning activities.55

Team Matrix

Time on task: 10 to 20 minutes; Group size: 2

When the instructor introduces new concepts that are similar, a team matrix can help students differentiate the most salient features of each idea. It presents a list of characteristics to student pairs, and students can determine which characteristic belong to each concept. All the students in the class can then discuss the answers to reinforce their understanding of the material.56

Think-Aloud Pair Problem Solving

Time on task: 30 to 45 minutes; Group size: 2

Students receive complex problems and develop solutions to solve them. One student is the problem solver who explains their thought process and the other student listens to their thought process and offers suggestions. When this process is complete, the students can switch roles.57

IF-AT Cards

Time on task: 5 to 15 minutes; Group size: 3 to 5

IF-AT (Immediate Feedback Assessment Technique) cards are similar to multiple-choice questions. However, with IF-AT cards, students can reveal the correct answer by scratching off the options on the card. This quiz method has two advantages: Students receive immediate feedback, and they can work in a team-based setting.

In this activity, students work on the questions individually without the IF-AT cards. The students then work collaboratively on the same questions and share their thoughts, reaching an agreement on what they believe are the correct answers. They scratch the card to find out if their answers are correct. The students scratch the card again if the answers are incorrect.58

Case Studies

Time on task: 1 to 2 hours; Group size: 3 to 6

Students are provided with a real-life scenario and apply what they learned to develop a solution as a group. They discuss potential ways of resolving the problem and what solutions to come up with. Strong case studies should involve a conflict and reflect the complexity of the situation.59

Three-Step-Interview

Time on task: 15 to 30 minutes; Group size: 2, then 4

This ice breaker and team-building exercise encourages students to internalize important concepts covered in textbook material or lectures. Typically, the instructor will pose questions that are based on course content, which do not have right or wrong answers. In this three-step interview, a student will interview their partner within a time limit set by the instructor. In the next step, the students will switch roles and conduct the interview again. In the third step, two pairs of students will form a group of four students, and the team members will introduce their partner’s ideas to the other group members. For pairs that are making faster progress, the instructor can add an “extension” activity, such as an extra question, to limit off-task conversations and give these groups an opportunity to work on challenging tasks.60

Send/Pass-a-Problem

Time on task: 30-45 minutes; Group size: 2-6

The starting point of this structure is a list of case studies, issues, or problems, that can be instructor-selected or student-generated. Each team notes down its assigned problem on the front of an envelope or folder. The teams then come up with solutions for these problems and write them down on a piece of paper. These solutions are placed in the envelope or folder and given to a different team. The second team’s students then brainstorm their own solutions without looking at the previous team’s ideas. The folder now contains ideas from both groups, and it is then handed over to a third team which reads the solutions, brainstorms their own, and then summarizes the suggestions from all three groups. This activity offers students the opportunity to engage in the evaluation and synthesis levels in Bloom’s taxonomy.61

Jigsaw Discussion

Time on task: 30-45 minutes; Group size: 2-6

The instructor breaks a general topic into smaller pieces. Each group member is asked to read and learn about a different topic. They then teach other group members about what they learned from their topic. After everyone has shared their knowledge, all students in the group have learned something important about the topic.62

Pro and Con Grid

Time on task: 15 to 30 minutes; Group size: 2-5

Students can list out the advantages and disadvantages of an issue. This activity develops students’ evaluative and analytical skills and encourages students to examine two sides to the problem while determining the value of opposing arguments.63

Brainstorming

Time on task: 15 to 30 minutes; Group size: 2-5

In this brainstorming activity, students brainstorm ideas which will be recorded by the instructor on the whiteboard. The instructor can introduce a new topic by starting with “tell me everything you know about…” Students’ comments can be organized into categories, or students can create categories and examine the importance of different interpretations and impressions. The main objective of brainstorming sessions is to write down all ideas and then offer critiques after the idea generation portion of the activity.64

Problem Solving

Time on task: 15 to 30 minutes; Group size: 2-5

The instructor can start a class with a paradox, a question, an enigma, or a compelling, unfinished human story. Depending on the field, an economic model, a mathematical proof, a scientific demonstration, a historical narrative, or the outcome of a novel’s plot may be required to determine a solution. During the lecture, the instructor can make references to the problem and encourage students to come up with their solutions in the story. The instructor can record students’ responses on the board and encourage discussion. For example, questions can include: “Which solution, outcome, or explanation makes the most sense to you?” “What do you think will happen?”65

Role Playing

Time on task: 15 to 45 minutes; Group size: 2 to 5

In this activity, students “act out” a role and get a better understanding of the concepts that are discussed.66 After the role play, the activity ends with a group discussion that identifies the approaches that group members took and the varying perspectives on a topic.67

Forum Theatre

Time on task: 15 to 45 minutes; Group size: 2 to 5

The instructor can use theater to describe a situation and ask the students to participate in the sketch to act out potential solutions. For example, if the sketch depicts an escalating interaction between a patient and nurse, the students can come up with solutions on how to deescalate. Finally, the instructors can ask students to act out the scene with the solution.68

Online Activities

Below are some examples of online options that can be assigned to students to prepare them for the in-class activities.

Online Readings

To prepare for the in-class activities, students can read an article, book chapter, or website. To motivate students to engage deeply with the reading, instructors can include annotations, guiding and reflective questions, and highlights of the reading’s main points.69

Screencasts

Screencasts are recordings that capture computer images and audio narration. They are usually used to demonstrate visually complex activities such as lab demonstrations, introduce complex concepts, and to review foundational course content. It is recommended that screencasts are between 10-12 minutes long, as students’ attention decreases after 10-15 minutes in a lecture. Instructors can include quizzes and guided questions in the screencasts materials to increase student engagement.70

Online Quizzes

Online quizzes can be helpful for gauging students’ understanding of the course content and make sure that they have a solid foundation of the threshold concepts covered online. They provide students with constructive and fast feedback. They can be a mix of multiple choice, short answer, and multiple select questions. The instructor can ask questions that go beyond simple recall or just testing for coverage of the material. The instructor can pose a final question that asks students what concepts were the most challenging for them which can be addressed in class.71

Online Discussions

- An instructor/TA can lead an online discussion that is relevant to the activity that students completed before class;

- Students can facilitate, start, or run a discussion that is related to what they have learned and how they can apply the knowledge;

- Students can use group discussion boards to formulate, develop, and articulate their ideas before sharing and presenting them to other students in class;

- Students can identify a question about the reading or online content for further discussion during class time.

Definitions and Terminology

Asking questions that test students’ knowledge on the meaning of new terminology and that help students to consider the words in more depth can lead to better understanding of the course content. The instructor can pose questions in an online discussion board or an online quiz.72

One Paragraph Summary

Students will do an online reading before writing a one-page summary or a paragraph, allowing the instructor to gauge students’ learning and address students’ questions or misunderstandings during class. Students can also practice their ability to summarize long texts.73

Critical Reading

The instructor can ask the students to submit a response to an assigned reading, which can be an article, a book chapter, or a research paper. For example, students can be asked to reflect and analyze the paper, or critically evaluate the ideas.74

Peer Review

By reviewing their peers’ work, students deepen, reinforce, and consolidate their own and their peers’ understanding of the course content. This can improve students’ critical analysis skills, and help them feel comfortable with receiving constructive feedback and justifying their position in class discussions. A peer review can be conducted on an online discussion board where students can view their peers’ submissions. The instructor will be able to identify the students’ understanding of their peers’ work and their critiques.75

Getting Ready for the “Just in Time Teaching (JiTT)”

After the online learning activity, the instructor can require students to share online feedback or ask questions about the content in the online materials. The instructor can then respond by creating Peer Instruction or JiTT activities based on students’ feedback for the in-class portion of the flipped classroom.76

Tools for Active Learning

Active learning can be incorporated into your course in a number of different ways. Check out the information below for some ideas to consider.

Tools for Exposing Students to Course Content Out of Class

Low-Tech

- Select textbook pages

- Journal articles

- Case studies

- Customized handouts

- Primary sources

- Lecture notes

High-Tech

- Screencasts

- YouTube Videos, TED Talks

- Interactive Canvas modules (also ensures accountability)

- Selections from previously captured lectures

Table adapted from The University of Michigan’s article on First Exposure to Course Content.

Tools to Ensure Students Complete the Preparatory Work

Low-Tech

- Paper quizzes

- Reflective in-class writing (at the beginning of class)

- Journal entries

- Submitting discussion questions on index cards as students enter

High-Tech

- Interactive modules

- Blog posts (UBC Blogs)

- Online forums

- Submitting discussion questions electronically

Table adapted from The University of Michigan’s article on Ensuring Accountability.

Tools for Implementing Active Learning

Low-Tech

- Discussions

- In-class problems

- Case studies

- Role-playing, simulations, etc.

- Group projects

- Peer review

High-Tech

- Using Canvas discussions to capture small group discussions

- Using Zoom to interact with disciplinary experts

Table adapted from The University of Michigan’s article on Active Learning in the Flipped Classroom.

Challenges and Solutions of Implementing a Flipped Classroom

Challenges:

Solutions:

1. Greater Workload for the Instructor

Creating instructional videos and preparing for pre-class and in-class activities can be tedious and time consuming. Another concern is ensuring equal access for students with accessibility needs.77

The instructor can reuse the instructional materials without too much extra effort if the class is offered again the following year.78 It is recommended to first look for existing materials for students to use before class, such as readings. To create accessible learning materials for a course, please visit this page on Accessibility in APSC on our website.

2. Course Content Might Need to be Reduced

Due to increased student participation, the instructor may not be able to teach as much content as in previous years. This means that the course’s learning outcomes need to be revised.

Although the long-held belief in academia is that teaching more content is better, low lecture density actually leads to more learning (measured by exam performance).79 Instructors can gradually slim down the content to the most important topics and use the remaining class time for active learning activities. The active learning component of a flipped classroom can help students retain concepts for a longer period of time and apply the concepts more effectively.80 Visit the Guide to Teaching for New Faculty in APSC on our website for more information.

3. Some Active Learning Activities Are Not Suitable for Large Classes

Some active learning activities may not be suitable for large classes, such as brainstorming or role-playing activities.

Although the options available to larger classes are slightly limited, there are different ways to encourage students to participate in peer learning and apply concepts. For example, IClickers, think-pair-share, and mini-lectures can be facilitated in large classes.81 The article, In-Class Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom, provides an overview of different learning activities suitable for different class sizes.

4. Student Challenges When Changing to a New Classroom Format

Although students may find being passive in a lecture less intimidating and easier than participating in active learning activities, students often understand that active learning strategies are more effective and create meaningful learning experiences.82

Instructors can encourage students to ask questions by creating a positive environment that makes students feel comfortable sharing their concerns. Scheduling office hours is one way of providing individualized help to students.83 Read this article for tips on supporting students.

5. Not All Students Come to Class Prepared

Some students may not come to class prepared due to various reasons, such as not finding the readings interesting, seeing a weak connection between succeeding in the course and doing course readings, believing that important concepts will be taught in lectures, or finding the readings too difficult.84

If students are unprepared for the in-class session or do not complete the pre-class activities, instructors can still move forward with the content. Once students notice that the instructor is serious about facilitating active learning during class, they will be more prepared for the next class.85 Check out this article on Motivating Students to Come to Class Prepared for more information.

6. Technical Difficulties

Using a new piece of technology often involves technical issues or blips along the way.

Take a moment with your students to check in and ensure that they know how to access the online materials, instructional videos, and other content on their own.86 Technical issues can – and do – happen at unexpected times, so keep in mind the resources around you, such as the Get Support page, that can offer timely support.

Footnotes

- University of Toronto, Scarborough Library. (n.d.). Digital Pedagogy – A Guide for Librarians, Faculty, and Students. https://guides.library.utoronto.ca/c.php?g=448614&p=3552449 ↩︎

- The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, University of Manitoba. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://umanitoba.ca/centre-advancement-teaching-learning/support/flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning, Yale University. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://poorvucenter.yale.edu/teaching/teaching-resource-library/creating-a-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- The Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning, Harvard University. (n.d.). Flipped Classrooms. https://bokcenter.harvard.edu/flipped-classrooms ↩︎

- Center for Teaching and Learning, UC Berkeley. (n.d.). Flip Your Classroom. https://teaching.berkeley.edu/teaching-guides-resources/designing-your-course/flip-your-classroom ↩︎

- Center for Teaching and Learning, UC Berkeley. (n.d.). Flip Your Classroom. https://teaching.berkeley.edu/teaching-guides-resources/designing-your-course/flip-your-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, University of Manitoba. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://umanitoba.ca/centre-advancement-teaching-learning/support/flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- Center for Teaching and Learning, UC Berkeley. (n.d.). Flip Your Classroom. https://teaching.berkeley.edu/teaching-guides-resources/designing-your-course/flip-your-classroom ↩︎

- Center for Teaching Innovation, Cornell University. (n.d.). Flipping the Classroom. https://teaching.cornell.edu/teaching-resources/active-collaborative-learning/flipping-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- Centre for Instructional Support, University of British Columbia. (n.d.). Team-Based Learning. https://cis.apsc.ubc.ca/teaching-strategies/team-based-learning/ ↩︎

- Centre for Instructional Support, University of British Columbia. (n.d.). Team-Based Learning. https://cis.apsc.ubc.ca/teaching-strategies/team-based-learning/ ↩︎

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). Sample Test Questions. https://www.nursingworld.org/certification/our-certifications/study-aids-ce/sample-test-questions/stq-medsurg/ ↩︎

- National Council of Architectural Registration Boards. (2024). Architect Registration Examination 5.0 Practice Exam: Project Planning & Design. https://www.ncarb.org/sites/default/files/ARE-Practice-Exam-Project-Planning-and-Design.pdf ↩︎

- Campbell, S. (2022, December 13). Urban planning 500: Planning theory fall 2022 study guide. The University of Michigan. https://websites.umich.edu/~sdcamp/urp500/examstudyguide.html ↩︎

- Center for Teaching and Learning, UC Berkeley. (n.d.). Flip Your Classroom. https://teaching.berkeley.edu/teaching-guides-resources/designing-your-course/flip-your-classroom ↩︎

- Center for Teaching and Learning, UC Berkeley. (n.d.). Flip Your Classroom. https://teaching.berkeley.edu/teaching-guides-resources/designing-your-course/flip-your-classroom ↩︎

- Center for Teaching and Learning, UC Berkeley. (n.d.). Flip Your Classroom. https://teaching.berkeley.edu/teaching-guides-resources/designing-your-course/flip-your-classroom ↩︎

- Center for Teaching and Learning, UC Berkeley. (n.d.). Flip Your Classroom. https://teaching.berkeley.edu/teaching-guides-resources/designing-your-course/flip-your-classroom ↩︎

- Center for Teaching and Learning, UC Berkeley. (n.d.). Flip Your Classroom. https://teaching.berkeley.edu/teaching-guides-resources/designing-your-course/flip-your-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, University of Manitoba. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://umanitoba.ca/centre-advancement-teaching-learning/support/flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, University of Manitoba. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://umanitoba.ca/centre-advancement-teaching-learning/support/flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, University of Manitoba. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://umanitoba.ca/centre-advancement-teaching-learning/support/flipped-classroom ↩︎

- Fostaty Young, S. (2021). Introduction to the ICE Model. In S. F. Young & M. Troop (Eds.). Teaching, learning, and assessment across the disciplines: ICE stories (pp. 1-7). eCampus Ontario. ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- The Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning, Harvard University. (n.d.). Flipped Classrooms. https://bokcenter.harvard.edu/flipped-classrooms ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- Center for Teaching Innovation, Cornell University. (n.d.). Flipping the Classroom. https://teaching.cornell.edu/teaching-resources/active-collaborative-learning/flipping-classroom ↩︎

- The Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning, Harvard University. (n.d.). Flipped Classrooms. https://bokcenter.harvard.edu/flipped-classrooms ↩︎

- Center for Teaching Innovation, Cornell University. (n.d.). Flipping the Classroom. https://teaching.cornell.edu/teaching-resources/active-collaborative-learning/flipping-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- Center for Teaching Innovation, Cornell University. (n.d.). Flipping the Classroom. https://teaching.cornell.edu/teaching-resources/active-collaborative-learning/flipping-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- Center for Teaching Innovation, Cornell University. (n.d.). Flipping the Classroom. https://teaching.cornell.edu/teaching-resources/active-collaborative-learning/flipping-classroom ↩︎

- Christie, T. (n.d.). Christina Bollo: A ‘flipped classroom’ for architecture students. Office of the Provost, University of Oregon. https://provost.uoregon.edu/christina-bollo-flipped-classroom-architecture-students ↩︎

- Ng, E. (2024). Investigating the impact of the flipped classroom on nursing student’s performance and satisfaction. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 19, 376-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2024.01.001 ↩︎

- Zehner, E. (2020, August 18). Curriculum design. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/articles/2020-08-acsp-curriculum-innovation-awards/ ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- Center for Teaching Innovation, Cornell University. (n.d.). Flipping the Classroom. https://teaching.cornell.edu/teaching-resources/active-collaborative-learning/flipping-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). In-Class Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/class-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). In-Class Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/class-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). In-Class Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/class-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- iClicker Student Mobile App. (n.d.). iClicker. https://www.iclicker.com/students/apps-and-remotes/apps ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). In-Class Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/class-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). In-Class Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/class-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). In-Class Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/class-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- Center for Teaching Innovation, Cornell University. (n.d.). Flipping the Classroom. https://teaching.cornell.edu/teaching-resources/active-collaborative-learning/flipping-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). In-Class Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/class-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). In-Class Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/class-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). In-Class Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/class-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). In-Class Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/class-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). In-Class Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/class-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, University of Manitoba. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://umanitoba.ca/centre-advancement-teaching-learning/support/flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, University of Manitoba. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://umanitoba.ca/centre-advancement-teaching-learning/support/flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, University of Manitoba. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://umanitoba.ca/centre-advancement-teaching-learning/support/flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, University of Manitoba. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://umanitoba.ca/centre-advancement-teaching-learning/support/flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, University of Manitoba. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://umanitoba.ca/centre-advancement-teaching-learning/support/flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, University of Manitoba. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://umanitoba.ca/centre-advancement-teaching-learning/support/flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, University of Manitoba. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://umanitoba.ca/centre-advancement-teaching-learning/support/flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, University of Manitoba. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://umanitoba.ca/centre-advancement-teaching-learning/support/flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). In-Class Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/class-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, University of Manitoba. (n.d.). Flipped Classroom. https://umanitoba.ca/centre-advancement-teaching-learning/support/flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Online Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/online-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Online Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/online-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Online Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/online-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Online Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/online-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Online Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/online-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Online Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/online-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Online Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/online-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Online Activities and Assessment for the Flipped Classroom. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/online-activities-and-assessment-flipped-classroom ↩︎

- Benjes-Small, C. & Tucker, K. (n.d.). Keeping Up With…Flipped Classrooms. The Association of College and Research Libraries. https://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/keeping_up_with/flipped_classrooms ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- Russell, I., Hendricson, W., Herbert, R. (1984). Effects of lecture information density on medical student achievement. Journal of Medical Education, 59(11), 881-889 ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning, Northern Illinois University. (2024, March 14). Supporting Underprepared Students. https://citl.news.niu.edu/2024/03/14/supporting-underprepared-students/ ↩︎

- Office of Teaching and Learning, University of Denver. (n.d.). Motivating Students to Come to Class Prepared. https://otl.du.edu/plan-a-course/teaching-resources/motivating-students-to-come-to-class-prepared/ ↩︎

- The Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Course Design: Planning a Flipped Class. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/course-design-planning-flipped-class ↩︎

- Edutopia. (2014, November 4). The Flipped Class: Overcoming Common Hurdles [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/bwvXFlLQClU?si=-MvdqFCEkGivUcQn ↩︎